The GST Compensation Cess: Problems & Solution

V Bhaskar and Vijay Kelkar 1

The Centre should promptly respond to the demand from states to pay them overdue compensation cess by borrowing from the market. Though it does not appear to be legally liable, it has a moral imperative to do so, even if the guaranteed rate of revenue of 14% is inordinately high in the present COVID led economic downturn. However, it must be remembered that the compensation cess was designed to be self- limiting. If state “losses” on account of GST continue, it means that the GST model should be restructured, not that the compensation template should be reviewed. A possible design for restructuring GST has been outlined in the paper, which should be linked to the payment of compensation cess. These reforms can best be led by an independent and professional GST secretariat to advise the GST council. It would be staffed by representatives of both the Centre and states and led by a taxation expert of national stature. The call to reform and prolong the GST compensation mechanism should not debilitate the GST.

The delay in payment of GST compensation has aggravated the fiscal stress of states already facing a COVID led revenue compression. States are demanding immediate payment of arrears. The compensation cess being collected during the present economic downturn cannot meet these rising demands. In its 40th meeting held recently; the GST Council resolved to meet in July solely to resolve this issue. This article examines the various dimensions of this complex issue which threatens to be an irritant in Centre State fiscal relations. Five options for payment of compensation revenue in the face of a bare Central fiscal cupboard are examined here. However, it must be remembered that the compensation cess was designed to be self-limiting. If state “losses” on account of GST continue, it means that the GST model should be reviewed, not that the compensation template should be tweaked. The call to reform and prolong the GST compensation mechanism must be resisted.

The paper is divided into eight Sections. Section 2 provides the rationale for the compensation cess. Section 3 examines its legal structure. Section 4 describes the experience of paying compensation cess when VAT was introduced in 2005. Section 5 examines the liability of the Centre to pay compensation in the face of falling cess collections. Section 6 examines the available options for meeting the demand of the states and makes recommendations. Section 7 makes the case for an independent GST Secretariat to implement these recommendations. Section 8 concludes.

-

The Compensation Cess structure

The Goods and Services Tax (Compensation to States) Act 2017(Act) was enacted simultaneously with the four other GST related Acts to guarantee a minimum revenue to states after the implementation of the GST. This Act has no organic relationship with the GST. Its need was felt for three reasons.

- A revenue neutral rate was supposed to have been put in place at the time of implementation of GST. While this would ensure that on a gross basis GST would be revenue neutral, individual states could suffer losses depending upon their consumption and production Large manufacturing states had voiced such concerns and they needed to be co-opted into the national consensus. The Act which guaranteed that states would be provided full compensation for the loss of their revenues convinced them to join the GST.

- The Centre in the past had not lived up to its commitments to provide compensation to states for the revenue loss they had incurred when the Central Sales Tax was phased out. This had led to the emergence of a trust deficit between the Centre and the This trust deficit could be bridged only by enacting legislation guaranteeing the payment of the revenue loss on the implementation of GST to the states.

- If the GST did not yield adequate revenue, one option would be to increase the GST rate. Such a choice would be difficult to implement The Act provided an alternate avenue to sustain revenue growth in states. Since it levies a cess on select luxury and sin goods, raising compensation cesses and expanding its base could be done in a more acceptable manner below the political radar1 .

The Compensation Act enables the levy of a cess on the CGST and IGST payable on specified goods and services. The proceeds are to be used for the payment of compensation to states for loss of revenue during the five-year period ending March 2022. The Act provides that the revenue loss for each state shall be determined as the difference between its actual revenue and its guaranteed revenue every year. The guaranteed revenue is to be determined assuming an annual nominal growth of 14% over the states revenues in the year 2015-16.

With the economy expected to contract during the current year, the 14% revenue growth assurance cannot be met now. The states feel that this commitment must be honored. The Centre feels that the guaranteed revenue should be revised downwards consistent with the falling compensation cess collections. This is the GST compensation cess problem.

It is useful to trace the genesis of the 14% assurance by reviewing the discussions in the meetings of the GST Council (GSTC), which has met forty times so far. The initial discussions about the compensation cess were held in the first and third meetings of the GSTC. They mainly centered around three issues. First the definition of the state’s revenue which was to be protected. Second the rate of growth to be guaranteed for this protected revenue during the transition period. Third, the base year from which this guaranteed rate was to be applied. The presentation made by the Department of Revenue during the 1st meeting proposed differential treatment to states. The average rate of growth of revenue collection over the preceding three financial years would be a states’ guaranteed revenue to be applied on the base year revenues . Several states broadly supported this proposal while suggesting variations in determining the rate of growth and the definition of revenue. The first meeting2 ended with the decisions on the base year (2015-16), the definition of revenue (all taxes subsumed into the GST) and the modalities of compensation payment (quarterly). Regarding the guaranteed rate of growth, the relevant extract of the minutes3 of the first meeting are placed below.

“.. the Chairperson noted that there were different possible approaches to the issue. One such approach could be to adopt a secular, common projected growth rate like 12% for the country. He observed that the advantage of the last methodology would be that special factors affecting revenue collection of a state like Jammu and Kashmir would be addressed. The Hon’ble Minister from Kerala opposed the last methodology but was agreeable to the suggestion of considering the best 3 growth rates out of the 5 years preceding the base year and excluding the two outliers. The Hon’ble Minister from Tamil Nadu did not favour this proposal. The Hon’ble Minister from West Bengal observed that the general consensus was to go for 6 years and take the best growth rate of3 years out of them. The Hon’ble Ministers of Assam, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana supported the idea of a secular growth rate and Uttar Pradesh suggested that the secular growth rate be pegged at 14%. The Hon’ble Minister from Tamil Nadu stated that projection of a secular growth rate could punish states whose tax administration collected taxes more efficiently. The Chairperson observed that this issue may continue to be discussed at official level and then, the issue could be brought back to the Council for a decision.”

It is notable that while most states had agreed to differential rates of growth depending upon their past performance, the Centre proposed a uniform rate of growth of 12% applicable to all states across the board in the country. This found favor with four states, one of which suggested that the guaranteed rate be 14% instead of 12%.

This issue was then revisited in the third GSTC meeting. The officers committee placed the following five alternate options for determining guaranteed revenue growth.

- Average revenue growth achieved in the three years ending 31st March

- Average revenue growth achieved in the five years ending 31st March

- Average revenue growth achieved in three years of the five years ending 31stMarch, 2016, excluding

- Fixed rate of 12% a.

- Rate equivalent to the nominal GDP growth rate of the country.

The officers committee recommended the fifth option for consideration. The discussion in the Council was sharply divided. A group of states pressed for adoption of the VAT model – each state to have a different growth rate depending upon its past performance. Others wanted a secular rate of 14-15% for all states. The Chairman pointed out that if the former method were adopted, the states’ guaranteed rates would range between 10%-18%. He felt that 18% was an unrealistic guarantee rate for any state. He also pointed out that the all India growth rate for the past three years was 10.6% “which was closer to reality”. He proposed a uniform rate 13% which “would be burdensome to the Central Government but would still be bearable”. Some states proposed this be increased to 14%. This figure was finally accepted apparently driven by the “decisions by consensus” modality adopted by the GSTC.

The GST Council discussed the legislation to couch these decisions during its 4th, 5th, 7th, and 8th meetings and finalized it in the 10th and 12th meeting. Some of these discussions will be referred to subsequently.

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be argued that the best option – guaranteeing revenue growth mirroring the nominal GDP growth of the country was not either examined or adequately discussed even though it was proposed by the Officer’s committee. Further the consensus on guaranteeing a 14% growth appears inconsistent with the then economic environment. This is demonstrated by Table 1 which shows the nominal growth rate of GDP – 2011-12 series4.

| Year | GDP Growth rate%age |

|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 13.8 |

| 2013-14 | 13.o |

| 2014-15 | 11.0 |

| 2015-16 | 10.5 |

| 2016-17 | 11.8 |

| 2017-18 | 11.1 |

| 2018-19 | 11.0 |

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Program Implementation, Government of India The Act was legislated in April 2017. Even assuming the buoyancy of the GST initially would be 1, there was no case at that time for guaranteeing a growth rate of 14%. Providing windfall compensation to the states even when the GDP growth numbers did not justify it appear to have effectively quelled any objections states could have raised on the Centre’s proposals on the structure and functioning of the GST Council, the design of the GST and its operational features . Once such a generous guarantee package was announced, incentives for state governments to press for an efficient and effective GST structure, weakened. The Centre’s incentive was to carry all the states along in the Council, even if, during this process, the GST was enfeebled. The officer’s committee which very competently analyzed recommendations before the GST did not have adequate credibility, as they were subordinate to and reported to the GST council members. What was missing during these discussions was an independent authority- a neutral and nonpartisan advisor whose sole interest would be to put in place an efficient and effective GST – or the least inefficient and ineffective GST. This is one of many examples of the need for an independent GST secretariat to provide credible, objective, and neutral advice to the GST Council. This issue is discussed subsequently.

- Legal Structure of the Compensation Act Sections of the Act relevant to this analysis are reproduced below. Emphasis has been supplied in bold capitals.

Article 7(1) of the Act reads:

The compensation under this Act shall be payable to any State during the transition period

Section 8(1) reads

There shall be levied a cess on such intra-State supplies of goods or services or both, as provided for in section 9 of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act, and such inter State supplies of goods or services or both as provided for in section 5 of the Integrated Goods and Services Tax Act, and collected in such manner as may be prescribed, on the recommendations of the Council, for the purposes of providing compensation to the States for loss of revenue arising on account of implementation of the goods and services tax with effect from the date from which the provisions of the Central Goods and Services Tax Act is brought into force, for a period of five years or for such period as may be prescribed on the recommendations of the Council:

Section 10 of the Act reads

- (1) The proceeds of the cess leviable under section 8 and such other amounts as may be recommended by the Council, shall be credited to a non-lapsable Fund known as the Goods and Services Tax Compensation Fund, which shall form part of the public account of India and shall be utilized for purposes specified in the said section.

- All amounts payable to the States under section 7 shall be paid out of the Fund.

- Fifty per of the amount remaining unutilized in the Fund at the end of the transition period shall be transferred to the Consolidated Fund of India as the share of Centre, and the balance fifty per cent. shall be distributed amongst the States in the ratio of their total revenues from the State tax or the Union territory goods and services tax in the last year5 of the transition period.

The Act was amended in August 2018 inserting Section 10 3(A) which partly reads Notwithstanding anything contained in sub section 3, fifty percent of such amount , as may be recommended by the Council which remains unutilized in the Fund at any point of time in any financial year during the transition period shall be transferred to the Consolidated Fund of India as the share of the Centre and the balance fifty percent shall be distributed amongst the states in the ratio of their base year revenue in accordance with the provisions of Section 5.

There are three distinct features in the Act. First, the guaranteed rate of 14% is applicable uniformly across the board to all states. Second the rate of compensation does not taper off over the reimbursement period. Third, the period of award is five years till 2022. The spirit of the Act is also clear. As outlined in Section 8(1) its sole purpose is to providing compensation to the States for loss of revenue arising on account of implementation of the goods and services tax. It has no other function. Ideally, it was expected that during every succeeding year the cess would be calibrated to nullify the closing balance if any in the compensation account during the previous year. Since such calibration is not possible after the terminal year (2021- 2022) when the Act lapses, it permits the closing balance of March 2022 to be distributed equally between the Centre and the States. The need for minimizing the collection of the cess is because it is not eligible for set off as input tax credit. It is subject to tax cascading -the very vice which was decried and cited as one of the reasons for the introduction of GST. Further the cess imposes an additional compliance burden on taxpayers. Thus, the base and the rate of the cess should be reduced wherever possible. If the compensation cess collected is more than the requirement of states, the proper course of action is either decrease its base or lower in its rate to reduce its fiscal footprint.

The opposite occurred. Even though it was running surpluses, the compensation cess rate structure was broadened and deepened. The Schedule to the Act initially proposed to apply the cess to only six items. These were pan masala, tobacco, coal, aerated waters, motor cars and designated supplies. The maximum stipulated rate was 15%. This list was subsequently expanded to cover 56 items. The maximum cess permissible was increased to 25%. The cess on luxury motor cars and cigarettes was increased. If sin goods were sought to be penalized, the proper course of action was to raise the GST rate for them, rather than levying compensation cess. This was not done.

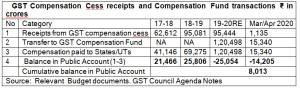

The above developments appear to indicate that the GST Council initially perceived the compensation cess to be a source of revenue rather than a cushion for stabilizing state revenues. Such an assumption is bolstered by Table 2 below which records the compensation cess collected and compensation paid to states since July 2017.

Table 2

As per Section 10(1) of the Act, the entire proceeds of the compensation cess need to be transferred to the GST Compensation Fund to be maintained in the Public Account. This was not done during the first two years 2017-18. The cess collection of ₹62,612 crores in 17-18 was credited to the Consolidated Fund and only ₹ 41,146 was paid to the states. The balance ₹ 21 ,466 crore has been recorded as GoI’s revenue during 2017-18. The excess of collection of compensation cess over compensation paid to states increased to ₹ 25,806 in 2018-19. This was also recorded as GoI’s revenue. It can be argued that for these two years, the Centre ’s GST revenue has been artificially increased to the extent of ₹47,202 on account of not crediting this amount to the public fund account as required by the statute. GoI complied with the legal requirement for crediting the GST compensation Fund in the Public Account only from the year 2019-20.

It appears that around August 2018, when compensation cess receipts far exceeded the requirements, the perspective of the Centre and the GST Council on the management of the compensation receipts altered singularly. Section 10(3) of the Act envisaged that any surpluses left over in the Fund only at the end of the transition period – i.e. March 2022 would be distributed equally between the Centre and the states. The August 2018 amendment to the Act, allowed for annual sharing of surplus in the Fund between the Centre and the states. The spirit of this amendment as well as the increase in compensation tax base and rates seem to point to two propositions. First, the cess was yielding more revenue than was required for its designated purpose and therefore free surpluses would be available. The cess, therefore could be a legitimate source of revenue. Second, such surpluses were envisaged continuously over the period up to 2022. Both these propositions go against the grain of the GST and the GST Secretariat did not remind the Council on the need to curtail rather than expand the scope of the compensation cess. It is of course a different story that this scenario changed spectacularly in 2019-20, when the economy turned sluggish and demand for compensation exceeded the revenue from the cess. If an independent Secretariat had been in place to advise the Centre and states of their obligations and ensure their compliance, the infractions listed above would not have occurred.

-

The VAT experience – Differentiation, Incentivization and Limitation

The model adopted6 for compensating states for loss of revenue when Value Added Tax (VAT) was implemented from 1st April 2005 was drastically different. It had three distinct features- differentiation, incentivization and limitation, which encouraged states to improve their collection efficiency. First, the revenue growth rate assumed was not uniform for all states. A ‘compensation’ growth rate was computed for each state which was the average of the revenue growth of best three of the preceding five years. Each state had thus a distinct guaranteed growth rate depending on its past revenue growth. Some states were eligible for a higher rate. Some for a lower rate. The states which showed high growth rates of taxes were rewarded and those with lower tax collection growth rates were penalized. Secondly the rate of compensation was 100% for the first year, 75% for the second year, 50% for the third year and nil thereafter. State VAT Commissioners were strongly incentivized to improve tax collection and achieve maximum growth as early as possible. This is because from the second year onwards, the state government would have to bear 25% of the computed losses. Pressed by demanding state finance departments, several state tax departments drew compensation only for the first year by quickly improving their collection efficiency. No compensation was drawn by them in the subsequent two years7 . Third, the period of compensation was restricted to three years. 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08. It terminated after the third year. A hard temporal constraint for compensation payments engendered an extremely focused tax department. The VAT Compensation payment model thus successful and none of the states asked for extension of the scheme. The three features of differentiation, incentivization and limitation ensured that states remained focused to improve their collection efficiency. None of these characteristics are present in the GST compensation scheme. It treats all states equally, the poor performers and the good performers. It gives them an assured rate of growth, which in the case of some states is significantly above their past revenue growth rate. The period of compensation is five rather than three years and the amount of compensation does not progressively decrease.

The lack of all three of these discriminators disincentivize states from putting in place improvements to the efficiency of the GST collections or proposing improved design and implementation methodologies to the GST council. For example, the GST system requires than audits be conducted after the annual return is filed by the dealer. Without the annual return there can be no audit. The annual returns for the year 2018-19 have not yet been filed by dealers. While risk-based audits are being conducted by some States, formal audits based on the annual return – as envisaged in the GST mechanism have not yet taken place. And states have no immediate incentive to do so given the overgenerous compensation package they are eligible for. An independent Secretariat could have pressed for a modality for prompt annual returns to ensure that audits take place. This would have checked the runaway claims on input tax credit reportedly being claimed by fly by night companies to the detriment of GST revenue.

-

The Centre’s liability to pay GST compensation

Section 18 of the Constitution 101 amendment Act reads “ Parliament shall, by law, on the recommendation of the Goods and Services Tax Council provide for compensation to the States for loss of revenue arising on account of implementation of the goods and services tax for a period of five years.” It is noteworthy that the provision for providing GST compensation does not find place in the Constitution. There is no constitutional guarantee for the payment of compensation cess. The Compensation Act was legislated separately for this purpose.

A combined reading of the Articles 7(1), 8(1) , 10(1) and 10(2) of the Act (detailed in Section 3 above) establishes two propositions. First the Centre does not pay and has no liability to pay compensation cess to the state governments. Second, the Centre merely manages the public fund account to which compensation cess is credited and from which the compensation is paid to states.

It is perhaps for these reasons that the Finance Minister announced in this year’s budget speech that “ It is decided to transfer to the GST Compensation Fund balances8 due out of collection of the years 2016-17 and 2017-18, in two instalments. Hereinafter, transfers to the fund would be limited only to collection by way of GST compensation cess.”

The Centre thus feels that the demand for compensation from states must be limited to the collections of compensation cess. If the latter falls short, then the Centre is arguing that it has no responsibility to fill the breach. Either the collection should be raised through rate increases or the demand should be reduced by revising the guaranteed rate downwards, or other modalities should be used for filling in the gap.

While the Centre’s position appears legally tenable, it does not appear ethically defensible for four reasons. First, its decision to restrict transfer to the Fund only to compensation cess collections seems more a fiscal aspiration than a legal compulsion. Section 10(1) of the Act allows for “other amounts” also to be credited to the Compensation fund with the approval of the GST Council.

Second, this issue was discussed in the 7th and 8th GSTC council meetings. One member worried that even if the amount available in the Fund was not sufficient to pay compensation, the States should be paid compensation for the five-year period. Another member wanted an explicit recitation in the Act that that if the amount for compensation was inadequate in the Fund, then the cess could be collected beyond the fifth year or to compensate for this shortfall. The final decision9 in this regard taken by the GSTC in its 8th meeting was as follows To modify Section 10(2) of the( then) Compensation Bill to clearly reflect that compensation shall be paid bi-monthly and that it shall be paid within 5 years, and in case the amount in the GST Compensation Fund is likely to fall short or fell short of the compensation payable in any bimonthly period, the GST Council shall decide the mode of raising additional resources including borrowing from the market which could be repaid by collection of cess in the sixth year or further subsequent year.

During the 10th meeting , when a member enquired why this modification was not made in the then current draft version of the bill, the Secretary stated that this modification was not required as Section 8(1) implicitly empowered the Centre to raise resources by other means for compensation which could be recouped by continuation of the cess beyond five years . He therefore proposed10 that the decisions taken enabling the GSTC to source market borrowing to pay compensation need not be incorporated in the law. The GSTC agreed to this suggestion. The draft of Section 10(2) of the Bill was thus not modified to include this concern.

However, minutes11 of the 8th meeting provides a clear guarantee.

The Hon’ble Chairperson assured that compensation to States shall be paid for 5 years in full within the stipulated period of 5 years and, in case the amount in the GST Compensation Fund fell short of the compensation payable in any bimonthly period, the GST Council shall decide the mode of raising additional resources including borrowing from the market which could be repaid by collection of cess in the sixth year or further subsequent years.

The Centre has thus given a commitment to state governments to pay compensation irrespective of the cess collections and now must adhere to it notwithstanding the fiscal pressure it may be facing. Trust and credible commitments are important pillars which sustain fiscal federal relations. A trust deficit arose when the Centre defaulted in payment of CST compensation to the states. This trust deficit should not be allowed to perpetuate itself. The Centre must deliver on its commitment, even if legally it does not have to and even if the compensation payable is overly generous in the present circumstances.

Third, in March and May 2020, the Centre increased the road and infrastructure cess and surcharge on petrol and diesel by ₹ 13 per litre. This is estimated to generate an additional annual income is about ₹ 2 lakh crore to the Centre. This amount is not shareable with the states. Since both the Centre and States share this tax base, ideally states should have got half this amount. Equity demands that the Centre compensate states for its unilateral preemption12 of their joint fiscal space.

Fourth, states are in the front line battling with COVID. Their revenues have dried up and they have been requesting the Centre to sanction COVID assistance grants to them. Central borrowing for providing GST compensation to states would proxy such grants .

-

Options available for meeting compensation demands

There are five possible options to meet the compensation cess shortage

- Lowering the guaranteed rate of compensation

- Increasing the compensation cess rates or widen its base

- Increasing the State share of the GST(SGST) at the cost of Centre’s share of the GST(CGST) leaving the overall GST rate the

- Borrowing by the GST Council from the market to meet the demand which would then be repaid by extending the period of compensation cess beyond

- Borrowing by the Centre from the market and crediting the compensation fund to the extent of the

The Chairman of the 15 Finance Commission in his presentation to the GSTC during its 37th meeting expressed concern about the sustainability of the guaranteed revenue growth rate of 14%. He underlined the increase in compensation demands made by the states in the light of the sluggish trends in the economy. He highlighted the need to reexamine the GST structure in view of its “cluttered rate structure, enormous challenges of compliance and challenges of technology.” His veiled plea to accept a reduction of the guaranteed rate to bridge the gap between cess collection and demand was vociferously rejected by members of the Council. Thus, the first option will find no acceptance.

The second option is equally untenable given the priority placed by both the Central and state governments to accelerate demand in a COVID racked economy. Raising the cess rates could dampen revival efforts. The GST council in its 39th meeting hesitated to rectify the inverted rate structure on footwear, textiles, and fertilizers by raising the rates on the final product for this very reason. Increase in the compensation cess would be equally unacceptable.

The third option cannot be examined in isolation since it proposes restructuring of the GST. This process needs to be accompanied by an intensive review of the existing structure of the GST and how the efficiency of the tax can be improved. The limited base, the convoluted rate structure, the unnecessarily complex IGST and its contentious appropriation, the increasing compliance burden on dealers placed by frequent changes in the law, the inertness of the GSTN mechanism and the mushrooming problem of fraudulent input tax credit transactions need to be addressed first.

The fourth option appears anomalous. The GST Council is a constitutional body created under Article 279A. It is not empowered to borrow. To enable it to do so may require giving it a corporate identity but in doing so, it may result in diluting its constitutional identity. This may not be prudent, given the approximately ₹ 12 lakh crore being presently collected under the various GST laws annually and the increasing tendency for litigation exhibited by most market players including GST dealers. In any case, any such borrowing needs to be guaranteed by the Centre, which will vicariously make it a Central borrowing.

This leaves the fifth option – the Centre borrowing and crediting the compensation fund to the extent of the shortfall. May be reluctantly, but ineluctably, the Centre must recognize that there is no other option till the cess expires in 2022. Perhaps it can negotiate a lowered guarantee rate with the states. But the Centre should also leverage this opportunity to ensure that states accept GST reform which could amongst others include the following steps to be implemented within a time frame:

- The inclusion of petroleum products in the GST base as required under Article 279A (5). A road map for enfolding electricity duty and real estate into the GST base

- The simplification of GST tax rates while minimizing Ideally, a “ reasonable ” single rate could be an effective counter cyclical initiative in today’s troubled times.

- A review of the unnecessarily complex structure of the IGST13 and its contentious appropriations which the C&AG has criticized. CGST, a tax levied by the Centre should be levied on all transaction across India – intra state and interstate. This is not the case now. Only intra state transactions are subject to CGST. Interstate transactions are subjected to This anomalous treatment leads to delays in input tax adjustment to consuming states. The present IGST taxes exports which is an anathema in a consumption-based GST.

- Treating all forms of goods transport similarly. Presently road transport is treated asymmetrically when compared to rail air and sea transportation of The proposed change will accelerate multimodal transport14 and strengthen supply chains. It will also lead to elimination of the e waybill.

- The IT structure of the GST has not performed effectively. Invoice matching appears to be an unattainable dream. Dealers have not yet filed annual returns for the year 2018-19. State / Central governments have been unable to undertake This has resulting in a freewheeling environment for dealers resulting in significant unverifiable input tax credit claims. The GSTN is a government company. It is ultimately responsible to its Board of Directors, not the GST Council. Its incentives may not always be towards improving the efficiency of the GST, as can be seen in the obstacles and problems it presently faces. This can only be addressed if the GSTN were to be made operationally responsible to the GSTC. This is not the case now.

-

An independent GST Secretariat

Presently the GSTC is serviced by a secretariat which is dominated by officials from the Revenue Department of the GoI. Its recommendations have limited credibility as its officials are subordinate to and report to the GST Council members. We have earlier discussed the inconsistency of allocation of Compensation Funds with the GST law as well as the absence of credible and objective advice at the time of deciding on the guaranteed rate for compensation. Other instances include the lack of depth in the agenda notes placed before the Council. For example, in the 23rd meeting, the GST rates for 178 goods were reduced from 28% to 12%. The agenda notes proposing these reductions made no mention of the tax base, the tax elasticity of the commercially important goods, the loss anticipated by such reduction and the anticipated increase in buoyancy through such measures. A rough and ready figure of losses anticipated was provided, with no basis. The credibility of this estimate was not verified by “truthing” such estimations by comparing them with actuals over the next six months. Such an exercise was not professional to say the least. The GST Council needs professional and independent advice on tax matters. This can only occur through the creation of an independent GST Council Secretariat which would provide neutral, unbiased, and pertinent advice on all the matters including those described above. The independent Secretariat should be headed by a Secretary General who should be a taxation expert of national stature. It could be staffed by representatives of both the Central and State governments. Presently, the GSTC secretariat has miniscule representation from the states. The Secretary General of the GST Council Secretariat should be the ex officio secretary of the GST Council. He would also be the ex officio Chairman of the GSTN which would improve its accountability. This Secretariat should be charged in the first instance to implement the reform initiatives outlined in Section 6 above.

-

Conclusion

The Centre should promptly respond to the demand from states to pay them overdue compensation cess by borrowing from the market. Though it does not appear to be legally liable, it has a moral imperative to do so, even if the guaranteed rate of revenue of 14% is inordinately high in the present COVID led economic downturn. However, it must be remembered that the compensation cess was designed to be self-limiting. If state “losses” on account of GST continue, it means that the GST model should be restructured, not that the compensation template should be reviewed. A possible design for restructuring GST has been outlined in the paper, which should be linked to the payment of compensation cess. These reforms can best be led by an independent and professional GST secretariat to advise the GST council. It would be staffed by representatives of both the Centre and states and led by a taxation expert of national stature. The call to reform and prolong the GST compensation mechanism should not debilitate the GST.

1 The compensation cess has been broadened and deepened since the Compensation Act was passed. 2 Minutes of the 1st GST meeting Para 37. The definition of revenue and modalities of payment were amended subsequently.

3 Ibid Para 38

4 http://www.mospi.gov.in/data .

5 As per Section2(1) (r) of the Act “transition period” means a period of five years from the transition date. I.e. 1st July 2022. Thus, this division of balances in the compensation fund was to have been undertaken only during 2021-22.

6 Ministry of Finance Department of Revenue F no 21/1/204-ST(PtII) of the 3rd February 2005

7 This was, of course, aided by a buoyant economy

8 The issue of balances due has already been examined in Table 2 above.

9 Minutes of the 8th GST council meeting Para 24

10 Minutes of the 10th GST council meeting Para 6.3

11 Minutes of the 8th GST council meeting Para 23(ii)

12 Such a unilateral preemption would not have been possible if petroleum products were in the GST base

13 “Reforming Integrated GST (IGST): Towards Accelerating Exports” by V Bhaskar and Vijay Kelkar. Policy Brief 2017, Pune International Centre, Pune.

14 “Reforming the GST: Do we need the e waybill?” by V Bhaskar and Vijay Kelkar. Policy Brief 2018, Pune International Centre , Pune.