Redesigning ULBs for Climate Action Draft_1

Redesigning Urban Local Bodies For Climate Action

Policy Paper 2022-2023

By

Prof. Amitav Mallik

Prithviraj Lingayat, Preeti Ahluwalia, Shantanu Ayachit & Megha Phadkay

(Team Energy, Environment & Climate Change Group,

Pune International Centre)

About this Paper:

This Policy paper puts forward the critical role of India’s Urban local bodies in tackling Climate change. The paper analyses the rising quantum of emissions that cities as hubs of economic activity contribute to and how ULBs can be empowered to mitigate them.

About Pune International Centre (PIC):

Pune International Centre (PIC) is a non-profit think tank which deliberates on issues of national importance. PIC has several verticals, namely, Social Innovation, National Security, International Relations, Energy Environment and Climate Change, and Economics.

Disclaimer:

This issue brief presents independent analysis. PIC does not have any commercial engagements. This study was done for policy advocacy purposes. The views expressed in this policy brief are those of the contributors/authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the PIC or the reviewers.

Editorial Team:

Prof. Amitav Mallik, Mr. Prithviraj Lingayat, Ms. Preeti Ahluwalia, Mr. Shantanu Ayachit, Ms. Megha Phadkay.

Suggested Citation:

Amitav Mallik, Prithviraj Lingayat, Preeti Ahluwalia, Shantanu Ayachit, Megha Phadkay. 2023. Redesigning urban local bodies for climate action, Pune International Centre.

March 2023

Preamble

India’s Own Problem

Urban local governance boasts great antiquity in the Indian context. From the Indus Valley Civilization to the 74th Constitutional Amendment of 1992, urban local governance has been a prominent feature in the public administration discourse in India. Today, India is on the brink of an urban revolution. Indian cities are the country’s growth engines, contributing nearly 60% to India’s gross domestic product (GDP), as per the 2022 report, Cities as Engines of Growth, by the NITI Aayog and the Asian Development Bank (ADB)1. Statistics and projections related to the urbanization trends in India are both staggering and worrying. For example, at present, 34% of India’s population lives in urban areas, with a growth rate of 2.4% in the 2010-18 period (World Urbanization Prospects, WUP, 2018). If this rate continues, the urban population in India will reach a whopping 600 million by 2030.

After China, India holds the largest ever urban population, more than 49 crore people live in Urban areas in India. The growth rate of India urban population is still higher than 2% per year, as opposed to China’s, which is less than 1%. Even though, the percentage of Indian population in urban areas is 35% of total, as opposed to 80% in United States of America, still India’s urban population is almost double of the American urban population. The cost here is that the carbon emissions have quadrupled in the last 30 years in India. Unfortunately, high economic growth, haphazard infrastructure development, improved access to the internet and smartphones, and escalating demand for vehicles has turned Indian cities into problems rather than solutions for the future which will be climate challenged.

According to the World Air Quality Report 2019, 21 of the 30 most polluted cities around the world are in India. Moreover, India was ranked as the 5th most vulnerable country to climate change by the Climate Risk Index 2019. These stark numbers have brought urban local bodies (ULBs) into the spotlight. Since one of the popular adages associated with climate action is “problems are global, but solutions are local”, the role of ULBs in facilitating the adaptation to the changing climate in a developing country like India cannot be overstated.

To sum up, Indian cities are growing at an unparalleled rate. This is causing massive issues in overall sustainability of the cities. Given this backdrop, this paper seeks to explore the multiple pathways through which urban local bodies can become active stakeholders in addressing the challenges thrown up by climate change. This cannot be done in isolation; it will require support from union and state governments in legislative and executive sphere. This will be an exceptional effort to empower the federalism in India.

The State of our Cities

Given that half of the world’s population started living in cities by 2007, it is no exaggeration to say that the battle against climate change will be won or lost in our cities. Cities currently occupy just 2% area and are responsible for about 70% emissions. In this context, it’s important to look at how many major Indian cities contribute to climate change by emitting CO2 and other GHGs.

Cities are home to over half the population of the world and contribute to 80% global GDP and up to 70% greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.. India’s top most 25 cities contribute to about 15% of the GHG emissions. Urban activities such as transport, buildings, industrial energy use are major source of GHG emissions in the cities.

Moreover, urban infrastructures are extremely energy intensive both in constructing it and using these structures – that is both embedded and operational emissions.

While cities are a major contributor, they are also affected greatly by climate change. Cutting down on emissions locally will not only help in improving urban air quality and reducing pollution, but also improve the overall wellbeing of the city dwellers. Islanding effects of tall, close buildings produce additional heating effects. Decentralizing climate action at city level can have significant impact on emission reduction and efficiency measures like including renewable energy, cleaner industrial activity, regulations, and incentives. The urban lifestyle itself is based on a high level of material and energy consumption which needs to change.

The current total emissions of India today are about 2.8 billion tonnes CO2eq.

Which the Cities directly contribute to climate change through different sources such as transportation, construction, high energy utilities, and waste management and are major sources of GHG emissions in the urban conglomerates.

| Sr No

. |

Metropolitan regions | State | Current Population | Adjusted CO2eq Emission Per capita

(T CO2 eq) |

Total CO2 eq Emissions of the city

(T CO2 eq) |

Optimal Total CO2 eq Emissions of the city

(2T CO2 eq) |

Difference | Percentage in excess |

| 1 | Pune | MH | 7,893,671 | 3.36 | 26,522,735 | 15,787,342 | 10,735,393 | 68% |

| 2 | Mumbai | MH | 20,961,472 | 2.21 | 46,282,930 | 41,922,944 | 4,359,986 | 10.40% |

| 3 | Delhi | DEL | 32,065,760 | 2.88 | 92,349,389 | 64,131,520 | 28,217,869 | 44% |

| 4 | Chennai | TN | 11,503,293 | 5.75 | 66,120,928 | 23,006,586 | 43,114,342 | 187.40% |

| 5 | Kolkata | WB | 15,133,888 | 3.95 | 59,748,590 | 30,267,776 | 29,480,814 | 97.40% |

| 6 | Bangalore | KAR | 13,193,035 | 2.68 | 35,304,562 | 26,386,070 | 8,918,492 | 33.80% |

| 7 | Hyderabad | TEL | 10,534,418 | 2.75 | 28,948,581 | 21,068,836 | 7,879,745 | 37.40% |

| 8 | Ahmedabad | GJ | 8,450,228 | 2.16 | 18,252,492 | 16,900,456 | 1,352,036 | 0.80% |

| 9 | Jaipur | RAJ | 4,106,756 | 3.47 | 14,252,086 | 8,213,512 | 6,038,574 | 73.52% |

| 10 | Lucknow | UP | 3,854,224 | 3.41 | 13,153,696 | 7,708,448 | 5,445,248 | 70.64% |

|

127,696,745 |

400,935,988 |

144,309,530 |

|

Total emissions of 10 cities combined |

400,935,988 |

GT CO2 eq |

Percentage of total

emissions |

14.31% |

|||

| Total emissions of India today (4000 cities) | 2,800,000,000 |

GT CO2 eq |

Table 1: Table 1 Projections of total CO2 eq emissions if cities in 2020

The above table summarizes the current trends in CO2 equivalent emissions per capita in India’s ten largest cities. The gap between real and optimal emissions per capita for each city may be seen. The percentage increase in excess emissions is shown in the last column which means that these 10 major cities have already crossed their threshold to tackle climate change.

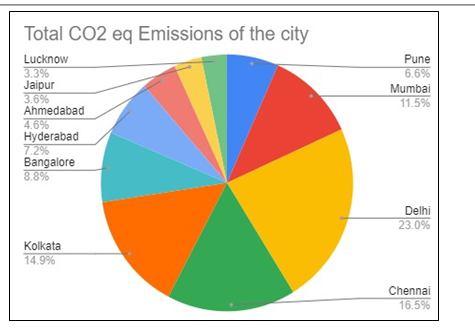

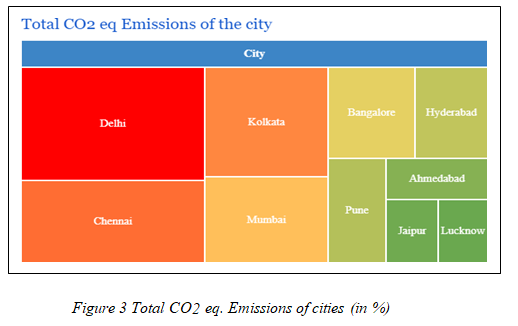

The graph above depicts the expected CO2eq emissions for India’s 10 major cities in 2020. With 5.75 TCO2eq emissions per capita, Chennai is now the largest emitter, while Ahmedabad has the lowest emissions per capita, with 2.16 TCO2eq. The CO2 emissions of the major cities are shown for the year 2022.

Figure 3 depicts the total CO2eq emissions of the 10 major cities of India. According to the data, Delhi is the largest emitter of CO2 in the country, with 92,349,389 CO2eq (23 %) of carbon dioxide emissions. The second-highest amount of carbon emissions at 66,120,928 CO2eq (16.5%) is Chennai, followed by Kolkata 59,748,590 CO2eq (14.9%), Mumbai 46,282,930 CO2eq (11.5%) and Bangalore 35,304,562 CO2eq (8.8%). The total emissions of the 10 major cities combined are estimated up to 400,935,988 GT CO2eq, while the total emissions of India today are about 2,800,000,000 GT CO2eq (for 4000 cities). For ten main cities in India, the difference between adjusted CO2eq emissions and expected total CO2eq emissions is 14.31914243. As a result, the Ten cities account for 14.31% of India’s overall emissions.

| City | Population forecast in 2030 | Projected CO2 eq emissions per capita 2030 (BAU) (TCO2 eq) | Total projected CO2 eq Emissions of the city 2030 (BAU) (T CO2eq) | Optimal CO2 eq Emissions of the city 2030 (T CO2eq) | Difference in 2030 | Percentage in excess in 2030 |

| Pune | 10,187,391 | 4.84 | 49,290,674 | 20,374,783 | 28,915,892 | 141% |

| Mumbai | 27,052,397 | 3.18 | 86,013,636 | 54,104,793 | 31,908,843 | 58% |

| Delhi | 41,383,337 | 4.15 | 171,624,974 | 82,766,673 | 88,858,301 | 107% |

| Chennai | 14,845,887 | 8.28 | 122,881,188 | 29,691,774 | 93,189,414 | 313% |

| Kolkata | 19,531,450 | 5.69 | 111,038,636 | 39,062,900 | 71,975,736 | 184% |

| Bangalore | 17,026,629 | 3.85 | 65,611,095 | 34,053,259 | 31,557,836 | 92% |

| Hyderabad | 13,595,479 | 3.96 | 53,798,942 | 27,190,958 | 26,607,984 | 97% |

| Ahmedabad | 10,905,671 | 3.11 | 33,920,999 | 21,811,342 | 12,109,657 | 55% |

| Jaipur | 5,300,085 | 5.00 | 26,486,520 | 10,600,171 | 15,886,349 | 149% |

| Lucknow | 4,974,173 | 4.91 | 24,445,237 | 9,948,347 | 14,496,890 | 145% |

| 745,111,900 | 329,604,999 | 415,506,901 |

Table 2 Projections of total CO2 eq. emissions of cities in 2030

Table 2 depicts the projected emissions trends for the 10 cities in the year 2030 for the business-as-usual scenario (BAU). The gap between real and optimal emissions per capita for each city may be seen. The percentage increase in excess emissions is shown in the last column which means that these 10 major cities would surpass their 2020 percentages. This not only highlights the urgency for immediate action but also presents us with a grave situation that we would face soon.

Figure 4 depicts the total CO2eq emissions of the year 2020 versus 2030. The additional rise in the emissions shown in the figure shows the significant rise in emissions if the current trends continue. As shown in the graph above, the increase in emissions is nearly doubled that of present emissions. Delhi is expected to have a 44% increase in excess CO2eq emissions in 2020, and a 107% increase in excess CO2eq emissions in 2030. Similarly, CO2eq emissions in Chennai are expected to grow by around 313% by 2030, compared to the current 187.4%.

The analysis thus shows the excess emissions of just 10 major cities in 2020 and 2030. The emission of only the 10 major cities of India accounts to about 14.31% to the total CO2eq emissions of the country. Similarly, one can estimate the amount of CO2 eq emitted from all the cities in India. Thus, if the BAU trends continue over the next decade, the window for making reparations may no longer be available.

The future trajectory of urban responses to climate change in India will be shaped by how local development and climate goals will be linked and prioritized. While a range of Indian cities are beginning to embark on identifying such linkages, a strategic understanding of interacting climate and development priorities, across governance levels, is yet to be developed.

A project- based approach is necessary but not sufficient as cities are not culminations of sites and projects but entail complex systems, interacting infrastructures, and socio-technical systems. Given the magnitude of change that Indian cities will face in the coming years, and their impending challenges of growing population inclusivity and vulnerability, this section outlines the considerations by which climate actions can be mainstreamed in urban areas.

The previous section emphasized on building overall resilience within communities to combat and adapt to the inevitable changes that will occur due to climate change. However, it is fundamental that the natural systems of the region also must be stable and effective. Thus, future-proofing our cities with climate smart solutions is a major requisite to maintain the environmental and ecological stability as well as long term sustainability.

The major step towards restoring ecological and environmental balance in the city is improving the natural sequestration capacity. The natural sequestration capacity can be improved by using climate-smart planning models for urban spaces.

- Urban greens: Urban forests, according to these studies, serve as key carbon sinks and storage. The net carbon sequestration of urban forests is positive when they are young, but it decreases as the forest matures. Hence completely relying on forest cover for carbon sequestration won’t be as effective. Having urban green areas in the cities can help sequester substantial amounts of carbon. Therefore, due to its large capacity and potential for carbon storage, urban forestry must be included in urban green planning and architecture along with improving the urban green cover in cities.

- Green infrastructures: green infrastructure includes all the natural, semi-natural and artificial networks of ecological systems in urban and peri-urban areas, such as forests, parks, community gardens, and street trees and lakes and ponds. Buildings consume about 40% of the city’s energy. Economic expansion and population growth clubbed together fuel a large need for infrastructure and building. These demands thus, present a good opportunity for city planners to achieve energy and cost savings in the next decades by incorporating energy efficiency measures and innovative building materials into newly constructed buildings. Hence, solutions like, installing green roofs and terrace gardens, solar powered infrastructures, energy efficient construction methods, waste management systems, etc. can help reduce the emission rates of cities significantly.

- Using regenerative models: In the current model, resources are extracted from various unsustainable sources such as mines, farmlands, rivers to provide our cities. This results in the contamination of our natural resources. Hence, shifting to a more regenerative model is the need of the hour. Thus, basing this model on the principles of circularity will bring in new innovative designs that reduce the waste, recycle materials and reuse resources to the forefront will increase the ability of the urban environment system to withstand future shocks and stresses.

Importance of the 74th Amendment

The first major step towards decentralization of power to urban local bodies was the passing of the 74th Amendment to the Constitution in 1992. This amendment provided constitutional status to urban local bodies and mandated the establishment of three-tier local government structures consisting of Municipal Corporations, Municipal Councils, and Nagar Panchayats in urban areas. The Act made important changes in the Constitution of India related to local self-government. Apart from adding the Twelfth Schedule and Articles 243-P to 243-ZG in Part IX-A of the Constitution, some of the other important provisions of the 1992 Act are as follows:

- Creation of Three Types of Local Governments: The amendment provides for the creation of three types of local governments at the urban level – Nagar Panchayats for areas in transition from rural to urban, Municipal Councils for smaller urban areas, and Municipal Corporations for larger urban areas

- Constitution of State Finance Commissions: The amendment made it mandatory for every State to constitute a State Finance Commission to recommend the distribution of taxes between the State government and the local governments.

- Reservation of Seats for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Women: The amendment provides for the reservation of seats in the local bodies for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and women.

- Constitution of District Planning Committees: The amendment provides for the creation of District Planning Committees to prepare development plans for the district, consolidating the plans prepared by the local governments and the departments of the State government.

Why ULBs need Empowerment – the 70/30 Rule

Urban areas of India, house 35% of the population but amount to 70% of total emissions due to its extremely diverse activities. This means, focusing our actions on small units — cities — to initiate Rapid Climate action. Decarbonization of cities hold the most important solution for India to reach its Climate targets. Urban local bodies are most connected institutions to citizens in India today, thus making them a key area of focus.

Chapter 1:

Why is Climate Action at the Grassroots Important?

1.1 Why Urban Local Bodies?

When it comes to emerging but critical challenges like climate change, the effects are felt differently across different regions. They vary based on a variety of factors like topography, microclimates, vegetation, so on and so forth. So does the ability to cope and adapt to these changes. Factors like infrastructure, socio-economic profile of the area and resource availability are multipliers.

Urban sprawl clubbed with the lack of adequate infrastructure and services predisposes the areas to environmental risks and hazards like flooding, extreme heat, and pollution. During disasters, local governments end up becoming the first responders. As the frequency of climate change disasters is on the rise- floods, forest fires, heat waves, etc. – local governments will be at the forefront of this situation. The local natural resource make-up of an area and its maintenance strategy will also require approaches tailored to those contexts. Thus, when it comes to mitigating and adapting to the climate challenge, building capacity and nurturing resilient communities, local governments need to be empowered.

For a bottom-up approach, improving the functioning of local bodies becomes even more critical. The main question, therefore, is whether Urban Local Bodies have adequate resources to fulfil their responsibilities. India will require approximately $1 trillion by 2030 to achieve the national goal on climate change which was announced at the Glasgow Climate Change Conference (COP 26). Cities, despite being major hubs of economic growth, are responsible for approximately 75% of global emissions. As India is still urbanizing, we need to tackle the problem at the source. Currently, there are close to 300 cities in India with a population of 1 lakh and urbanization is increasing at a rapid pace. Each of them will require at least $3 billion till 2030 to take climate action. The amount will vary with factors like area, population, capacity, vulnerabilities and so on.

ULBs do not just include the city municipal corporations. Although the Municipal corporations are the most important urban administration bodies, there are other important development authorities such as NHAI, Metropolitan Region Development authorities such as PMRDA or MMRDA, MPCB, Forest department, MSEB, etc. All these authorities have executive jurisdiction in the cities. Therefore the paper concerns all these departments in the role they plan in administrating cities, these authorities need to work in unison to achieve the goals set out in this paper. The impact of every agency will depend on the finance and authority available to them.

The 12th schedule of the 74th Constitutional Amendment defined 18 functions of Municipalities.

They are as follows:

- Regulation of land use and construction of land buildings

- Urban planning including the town planning

- Planning for economic and social development

- Urban poverty alleviation

- Water supply for domestic, industrial and commercial purposes

- Fire services

- Public health sanitation, conservancy and solid waste management

- Slum improvement and up-gradation

- Safeguarding the interests of the weaker sections of society, including the physically handicapped and mentally unsound

- Urban forestry, protection of environment and promotion of ecological aspects

- Construction of roads and bridges

- Provision of urban amenities and facilities such as parks, gardens and playgrounds

- Promotion of cultural, educational and aesthetic aspects

- Burials and burials grounds, cremation and cremation grounds and electric crematoriums

- Cattle ponds, prevention of cruelty to animals

- Regulation of slaughterhouses and tanneries

- Public amenities including street lighting, parking spaces, bus stops and public conveniences

- Vital statistics including registration of births and deaths.

All 18 functions do not have a source of finance, while the municipal corporation is expected to take care of all functions. Thus, ULBs are overburdened with expenditure responsibilities but have constrained revenue- raising capacity. Challenges like climate action, climate adaptation and mitigation are not even a part of their mandate.

Some functions that fall under the aegis of climate action that ULBs could adopt:

| Mandating | Investing | Protecting |

| Setting energy efficiency standards | Investing in sustainable public transport | Conservation of key ecosystems for carbon absorption |

| Changing building codes to encourage low carbon infrastructure | Encouraging use of renewable energy | Adopting a mixed infrastructure model- green, blue and grey infrastructure to build resilience |

| ‘Greening’ the government procurement process | Incentivizing low-carbon innovations | Incentivising social forestry practices |

| Mandating use of renewable energy in new buildings | Setting up carbon trading markets | |

| Adopting a carbon tax to fund low carbon development | Creating employment opportunities by initiating |

1.2 How relevant is State level action?

Indian states have started taking action to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change. Many States have prepared State Action Plans on Climate Change (SAPCCs) as an attempt to mainstream climate action. There are a lot of investments happening in the Energy sector by different states like Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Bihar, Chhattisgarh etc. For example, Bihar invested 200-megawatt grid-connected ground-mounted solar power plant, funding grid connected solar rooftop capacity for health centers and education institutes; Chhattisgarh is expanding the use of solar water pumps among the state’s farming community, 100 crore for setting up 10,000 solar pumps under the Pradhan Mantri Kusum Yojana. Gujarat is setting up large scale renewable energy projects and building solar rooftop capacity. Apart from that, there are examples of state governments trying to restore the quality of the environment and trying to make it a viable business model. Where Himachal Pradesh Is pushing to develop its eco-tourism industry by developing nature trails, afforestation, soil conservation and water conservation; Jharkhand is planning to turn a biodiversity park in Namkum to an eco-tourism park eco-tourism park under a public-private-partnership model.

But these initiatives are piecemeal and far and few in between. Many of them aren’t even in cities where there is a need to tackle these challenges. These programs are also top-down in nature, i.e, the needs of the residents and their capacities are not taken into account while devising these plans. There is a need for sustained and systematic climate action at the local level.

The 74th Amendment was an acknowledgement of the need to decentralize certain functions. As India is still urbanizing, this is an opportunity to do it in a way that takes economic growth, job creation and social development into account.

The needs, situations and capacities of each city is different. Thus, each jurisdiction is going to need a different approach. This said, local governments in India resource-constrained and in need of personnel. This calls for the need to develop their capacities in terms of 3 Fs- Functions, Functionaries and Finance so they can create a range of possible futures for themselves. When there is competition between different cities and citizens have the choice to move if they’re dissatisfied with the service of one city, it can act as a force to improve municipal performance.

1.3 Where does the Challenge Lie?

Climate action cannot only be the prerogative of Union and state governments. Local governments are the closest to the citizens in terms of service delivery and basic utilities. Local knowledge and community participation need to be harnessed. Hence, they need to be at the forefront of initiating climate action without top-down diktats of union and state level governments.

The principle of subsidiarity is a guiding principle in designing government systems. It means that decision-making power should be devolved to the most appropriate level of governance, such as the individual, community, or local government. The goal here is to ensure a higher degree of accountability.

1.4 What do our Cities Need?

Cities need to become sustainable and livable and hubs of innovation. For this, environmentally sensitive development must be prioritized.

There are many layers of legislation and overlapping mandates among the large number of institutions and administrative bodies involved in urban climate action. There is a need for more institutional clarity, inter-agency coordination, and multi- disciplinary expertise to solve urban challenges.

This is the reasoning behind the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by all parties of the United Nations. Cities can become the drivers of sustainable development. SDG 11 aims to “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. A host of targets are dedicated to dealing with challenges specific to urban settings. These include:

SDGs are not isolated but are interlinked based on the contexts. There is a need to integrate SDGs into existing and new urban missions that are planned by Union or State governments for ULBs to implement. Multiple schemes like Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT), Smart cities, Swacch Bharat (Urban) have the scope to weave sustainability while local planning and implementation.

1.5 An Urgency for ULB Reforms

In recent years, there has been a renewed focus on urban governance in India, particularly in the context of sustainable development and climate action. There are ongoing efforts to enhance the capacity of urban local bodies to plan and implement sustainable development initiatives, and to integrate climate change considerations into urban planning and decision-making processes. However, as mentioned in a previous section, the devolution of powers to urban local self-government bodies in India has been insufficient and arbitrary. If ULBs are to become integral forces of change in climate adaptation and mitigation, several key reforms need to be undertaken with high urgency. Some of the most important are listed here:

- Financial empowerment: The local governments in India still face significant financial constraints, with limited sources of revenue and dependence on State governments for funds. There is a need to strengthen the financial autonomy of local governments by providing them with more sources of revenue, such as property tax, and enabling them to raise funds through bonds.

- Capacity building: Local governments often lack the technical and administrative capacity to effectively carry out their functions. There is a need to provide training and capacity-building programs to the elected representatives and officials of the local governments to enable them to carry out their responsibilities effectively.

- Expanding citizens’ awareness and participation: The 74th Constitution Amendment Act envisaged a significant role for citizen participation in the governance of local areas. However, there is a need to improve the mechanisms for citizen participation to ensure that citizens can meaningfully participate in decision-making processes.

- Stringent accountability mechanisms: There is a need to strengthen accountability mechanisms for local governments to ensure that they are accountable to citizens for their actions and decisions. This can be done through the creation of independent institutions, such as ombudsmen or local government audit bodies, to oversee the functioning of local governments.

Chapter 2: Current Structure of ULBs in India

2.1 History of Urban local governance in India

The origins of urban governance systems in India can be traced back to the ancient period. Starting with the writings during the Vedic period, primitive forms of local self-government can be found through the records of foreign travelers such as Megasthenes and treatises such as Kautilya’s Arthashastra. Local self-government was an important element of the social organization during the Buddhist period. The epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharat, also contain information about local guilds or paura, nigama, and gana. As provincial administration became central to governance, the system of local self-government strengthened further during the Mauryas and later the Guptas. The advent of the Mughal rule saw local administration become more autocratic. The kotwal was the nodal officer managing the large cities built by the Mughal emperors. The functions performed by the kotwal included maintaining roads and houses, levying, and collecting taxes, ensuring strict adherence to weights and measures, keeping a check on prices, and implementing laws.

The modern municipal administration in India was the work of the East India Company, which started off as a commercial body but eventually took on an exclusively administrative role in the early 19th century.

Urban governance systems kept developing as the EIC consolidated its rule in India. The next landmark event that gave a huge impetus to municipal administration in the country was the famous resolution issued by Lord Ripon, the then Viceroy of India, in 1882. Hailed as the Magna Carta of Local Self-Government, the resolution sought to achieve two objectives: one, to provide “adequate resources which are local in nature and are suited for local control, should be provided to local bodies”; and two, to encourage local governments to suggest measures, legislative or otherwise, so as to strengthen and deepen local self-government systems in the country.

The next stage of evolution in urban local governance came with the enactment of the Government of India Act of 1935, under which provincial governments gained importance. With Indian political parties, mainly the Indian National Congress (INC) winning several major provinces, the call to improve the governance and financing of municipal corporations became louder. Unfortunately, not much could be done during this period as Indian ministers resigned after the British dragged India into the Second World War without consent.

2.2 From 1947 to 1992

The years following independence, right up to 1992, presented an interesting stage in the evolution of municipal administration in India. For example, in 1948, the newly formed central government appointed the Local Finance Inquiry Committee to study and recommend the ways and means of improving the financial resources of local bodies. In 1954, the Central Council of Local Self-Government was constituted under Article 263 as an advisory body. It was not until 1985 that independent India’s first commission on urban management was constituted. Called the National Commission on Urbanization, it submitted its report in 1988, making a slew of recommendations on urban management. The report of the commission served as a prelude to the Constitution (74th Amendment) Act of 1992.

Important provisions of the 74th Constitution Amendment Act, 1992

The enactment of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA) in 1992 was a turning point for municipal administration in India. The following changes were made to the Constitution by the Act:

- It added a new part to the Constitution, Part IX-A

- It added the Twelfth Schedule to the Constitution

- It added Articles 243-P to 243-ZG in Part IX-A of the Constitution

These additions put in place an institutional framework for the effective functioning of ULBs in India, which was completely absent before. Certain specific aspects of the Act are worth looking at, as they reflect the essence of the legislation.

Article 243S: Wards Committees

Constituencies are divided into wards and therefore, Wards Committees, which represent the wards, are central to urban administration. Article 243S thus makes the following provisions:

- There shall be constituted Wards Committees, consisting of one or more Wards, within the territorial area of a Municipality having a population of three lakhs or more.

- The Legislature of a State may, by law, make provision with respect to

- the composition and the territorial area of a Wards Committee; and

- the manner in which the seats in a Wards Committee shall be filled.

- A member of a Municipality representing a ward within the territorial area of the Wards Committee shall be a member of that Committee.

- Where a Ward Committee consists of

- one ward, the member representing that ward in the Municipality; or

- two or more wards, one of the members representing such wards in the Municipality elected by the members of the Wards Committee, shall be the Chairperson of that Committee.

- Nothing in this article shall be deemed to prevent the Legislature of a State from making any provision for the Constitution of Committees in addition to the Wards Committees.

Article 243W: Powers, authority, and responsibilities of municipalities

The article defines what the powers of municipalities are, what kind of authority they would possess, and what their responsibilities would be.

The article thus states that

“Subject to the provisions of this Constitution, the Legislature of a State may, by law, endow:

-

- the Municipalities with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as institutions of self-government and such law may contain provisions for the devolution of powers and responsibilities upon Municipalities, subject to such conditions as may be specified therein, with respect to:

– the preparation of plans for economic development and social justice;

– the performance of functions and the implementation of schemes as may be entrusted to them including those in relation to the matters listed in the Twelfth Schedule. - the Committees with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to carry out the responsibilities conferred upon them including those in relation to the matters listed in the Twelfth Schedule”.

- the Municipalities with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as institutions of self-government and such law may contain provisions for the devolution of powers and responsibilities upon Municipalities, subject to such conditions as may be specified therein, with respect to:

2.3 Current structure of urban local bodies

The original Constitution contained detailed provisions for setting up democratic systems, structures, and processes at the central and state levels. However, urban local self-government found no explicit mention in the Constitution. Even the formation of village panchayats was added to the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs), but urban local bodies did not find a place in the DPSPs. The only indirect reference to urban local governance was in Entry-5 in the State List, which put the onus of forming local self-governments on state legislatures. As a result, from 1947 to 1992, India essentially continued the municipal system installed by the British. Finally, in 1992, when the 74th Amendment Act was passed, urban local government bodies got the much-needed (and much-delayed) constitutional status. At present, all aspects of urban management are governed by the provisions of the 74th Amendment Act. We will first look at the structural mechanisms of the 1992 Act and then comprehensively identify gaps that are hindering the transformation of ULBs into climate-change-fighting bodies.

Composition

A municipal area or a city is divided into wards, based on the population of that city. For each ward, those eligible to vote elect a representative called either ‘councilor’ or ‘corporator’. A corporator serves a term of five years. Every municipal corporation has a mayor, who is the nominal head of the corporation and is appointed by the political party that wins the corporation elections. The administrative head of a municipal corporation is the Municipal Commissioner, who is appointed by the state government and is usually an officer of the Indian Administrative Services (IAS).

2.3.1 Challenges facing Urban Local Bodies in India

The present structure and functioning of ULBs in India follow a top-down approach, with municipal bodies being dependent on the state government for finances and functional autonomy. This incomplete and arbitrary nature of the devolution of power has rendered ULBs mere implementation agencies, having little say in policy formulation. As a result, these bodies have limited space to participate in climate policy strategies and are mostly involved in basic administrative work.

Poor functional autonomy of ULBs

The whole idea behind giving urban self-governance bodies constitutional status through the 74th CAA was to facilitate a substantial devolution of powers to the urban populace. According to the 1992 Act, 18 functions have been allotted to ULBs, which they are now mandated to perform. This allotment, unfortunately, is in the hands of state governments and this is one of the key areas where several states have fallen short. A 2013 report by the Government of India revealed that only 11 out of the combined total of 31 States and Union Territories of India had transferred all of the 18 functions to ULBs. Furthermore, several municipal bodies have been deprived of town planning, which is one of their core functions, as it allows ULBs to mobilize resources and deliver essential public goods and services. Even one of the most prosperous municipal corporations of India, the Greater Mumbai Municipal Corporation is responsible for urban governance in the Greater Mumbai region, lacks substantial powers related to urban planning and land-use regulation because it does not have any independent authority to lease land and to accrue revenue independently (IGSSS, 2019). The trend is similar for even functions as basic as water supply, which should ideally be in the domain of ULBs but are still being performed by either the state government or parastatal agencies.

Irregular Elections

As per the 74th CAA, every municipal body shall have a term of five years, meaning that municipal elections would need to be conducted every five years unless the body dissolved before the expiry of its term. Municipal elections are the responsibility of the respective State Election Commission. However, the provisions for all matters related to municipal elections are made by the concerned state legislature. This feature of the act has been violated several times by state governments, dissolving municipal bodies and holding elections according to their convenience. State Election Commissions do not have the necessary powers to force state governments to hold regular municipal elections and have had to take the judicial route to perform their constitutionally mandated functions. For instance, in 2019, the Telangana State Election Commission complained to the State High Court that the Telangana State Government was deliberately not making arrangements for elections for ULBs after the expiry of their term. Many such instances continue to plague urban local governance, and, as a result, the quality of municipal administration remains shoddy.

Lack of financial autonomy

The biggest hurdle in the efficient functioning of ULBs in India is their financial dependence on the state government and the central government. The power to determine sources of finance for municipal bodies rests with the concerned state governments, such as authorizing a municipal corporation to levy, collect, and appropriate taxes, duties, tolls, and fees. Moreover, even if a state government allows a municipal corporation to collect and appropriate certain taxes, there is no guarantee that the civic body will be able to keep the proceeds of such taxes. In 2019, for example, a study by the Indo-Global Social Service Society (IGSSS) showed that in Hyderabad, property taxes from the most prosperous parts of the city were cleverly kept by the state government through the Industrial Township Law. The lack of financial independence, therefore, is a massive roadblock for ULBs, created by the undue fiscal power vested in the hands of state governments.

Thus, the above limitations can be divided into three broad heads – functional, political, and financial. Together, they have severely affected the quality of municipal administration, which, in turn, has deteriorated the quality of life in urban areas. With the effects of global warming and climate change intensifying, reaching solutions to these structural and operational challenges should be the top priority for the central and state governments.

2.4 Why cities should focus on the Environment

The development and expansion of urban areas in India have come at a cost to the environment. The establishment of a city requires the cutting down of forests and draining of swamps and other local water bodies. Once a city starts expanding as an increasing number of people migrate, several other development processes need to be undertaken, such as the paving of roads and the erection of residential buildings and commercial complexes, among others. These activities emit a wide variety of pollutants into the air, generate huge volumes of waste daily, and contaminate water and soil. The absence of trees and natural water bodies, both of which act as natural carbon sinks, leads to a steady accumulation of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, posing a constant threat to the individual as well as public health. For example, air pollution has been a major contributor to a variety of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. a 2019 study published in The Lancet found that more than 1.2 million deaths in India were caused by air pollution in 2017. As per the study, air pollution was the third leading risk factor for premature deaths in India, right after high blood pressure and smoking. Similarly, according to a 2018 study published in The Lancet, nearly 0.2 million deaths in India were attributable to water contamination in 2015. A 2019 study published in the Journal of Water and Health estimated that around 40,000 infant deaths in India every year are attributable to polluted water. Preventable waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea, cholera, and typhoid, were responsible for these deaths, as pointed out by the study. Urban local bodies, which are at the core of urban development processes, need to adopt sustainable practices to ensure minimal environmental impact while also adhering to the overall goal of development.

In sum, the environment should be a priority for ULBs in India for several reasons, including:

- Health: A clean, green, and healthy environment is imperative for public health. Bad air quality, polluted water, and inefficient waste management can collectively cause a variety of health problems, including respiratory diseases, water-borne afflictions, and vector-borne diseases.

- Quality of life: A green environment can improve the quality of life for the urban populace. Green spaces, such as parks and gardens, provide opportunities for recreation and relaxation, as well as transform into biodiversity habitats. These are critical elements for ensuring urban residents become responsible participants and conscious stakeholders in the process of sustainable development.

- Climate change: Cities are major contributors to climate change, but at the same time, they are also extremely vulnerable to its impacts. Therefore, investments in environmentally sustainable practices can help cities reduce greenhouse gas emissions, increase resilience to climate change, and enhance their capacity to adapt to climate variability.

Legal obligations: India has several environmental laws and regulations, including the National Green Tribunal Act, which mandates the protection and improvement of the environment. Cities are legally obligated to comply with these regulations and ensure the proper management of their environment.

Chapter 3: Laws Governing Urban Local Bodies in Environmental Jurisprudence

In analyzing the Role of ULBs in Climate Governance, two aspects are of concern:

(i) functions transferred to Urban Local Bodies in the wake of 74 th Amendment of the Constitution and (ii) adequacy of resources transferred to perform these functions

3.1 The connection of ULBs with Central and State Governments

Decentralization in governance started with the Constitution (Seventy-third Amendment) Act, 1992 and the Constitution (Seventy-fourth Amendment) Act, 1992. They provided constitutional status to the rural and urban local bodies respectively through devolving powers, functional responsibilities and authorities to them. In the current system of governance, Urban Local Governments are the third tier in the governance structure; and these are closest to address the needs of the citizens directly.

ULBs are established under the Constitution of India (under the 74th Amendment), and their functioning is governed by various laws and regulations. They are closely connected to both the Central and State Governments in India, as they receive funding and guidance from both levels of government.

3.1.1 Connection with Central Government:

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) is the nodal ministry of the Central Government responsible for urban development and management in India. MoHUA plays a crucial role in the development of ULBs by providing financial assistance, technical support, and policy guidance to them. Some of the key schemes and programs initiated by the Central Government to support ULBs include:

- Smart Cities Mission

- Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT)

- Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Mission)

- Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY)

- National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM)

3.1.2 Connection with State Government:

Each State in India has its own legislation for the establishment, composition, and functions of ULBs. State Governments play a vital role in providing guidance, supervision, and support to ULBs in their respective states. Some of the key functions of State Governments in relation to ULBs include:

- Formulation of State-level policies and guidelines for urban development and management

- Devolution of funds and functions to ULBs

- Appointment of Municipal Commissioners and other officials to ULBs

- Conducting of elections to ULBs and overseeing their functioning

- Monitoring and evaluation of the performance of ULBs

In conclusion, ULBs in India are closely connected to both the Central and State Governments, and their functioning is regulated by a complex network of laws, policies, and guidelines. Both levels of government play a critical role in providing financial, technical, and policy support to ULBs, and in ensuring that they are able to fulfill their mandate of providing basic civic amenities and services to citizens living within their jurisdiction.

But a recent report from RBI has raised concerns over the state of municipal finances in India, especially of urban municipalities, saying that they are becoming increasingly dependent on grants from state and central governments rather than relying on their own revenues.

3.2 Administrative hierarchy and Division of power

Early scholars, like K.C. Wheare, writing in the area of fiscal federalism suggested that different tiers of government in a federal polity should be coordinate with each other rather than one being subordinate to another.

The essence of federalism is mutual inter-dependence rather than mutual independence, though inter-dependence often turns out to be dependence of so-called lower tier jurisdictions on higher ones (M.J.C. Vile is quoted by Reagan, 1972, p.11).

The interface between State and Local Government can be observed when the State Government and Urban Local Government interact with each other in administrative functions, resource mobilisation, and implementation of State or Central Government policies or schemes or reforms. In administrative functions, the State Government departments, state line agencies and state-owned PSUs guide, support, and review functions of the Urban Local Government.

ULBs are included in the State List of the Seventh Schedule as item number 5, which reads:

“local government, that is to say, the constitution and powers of municipal corporations, improvement trusts, district boards, mining settlement authorities and other local authorities for the purpose of local self-government or village administration.”

While the Legislatures of the unit States are given exclusive power, under Article 246 (3), to legislative items in the State List of the Seventh Schedule and power to legislate on items, with some restrictions, in the Concurrent List of the said schedule, legislation in the matter of local self-government fell in the exclusive jurisdiction of the unit States. It was therefore expected of the State Legislatures and the State Governments to constitute and empower by legislation the local bodies so that they could act as the units of self-governments.

Part XI of the Constitution deals with the relationship between the Union and the States and it has two chapters—Chapter I dealing with legislative relations and Chapter II dealing with administrative relations.

Of the eleven articles dealing with legislative relations, clause (3) of Art. 246 of the article stipulates exclusive power to the State Legislatures to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in List II in the Seventh Schedule while the clause (2) stipulates co-extensive power to the State Legislature along with the Parliament with respect to any of the matters enumerated in List III in the Seventh Schedule.

All subject matters related with local functions are listed in List II and List III and traditionally local powers of raising resources (taxes, user charges and loans) are also listed in the List II. As the local bodies are not legislative bodies (but only deliberative bodies), local bodies do not have any exclusive domain of their own. Their domain is coextensive with and a subset of the state’s functional domain.

Art. 243W suggests that

“the Legislature of a State may, by law, endow the municipalities with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as institutions of self-government” and further suggests that.

“such law may contain provision for the devolution of power and responsibilities upon municipalities—subject to such conditions as may be specified—with respect to

(i) the preparation of plans for economic development and social justice and

(ii) the performance of functions and the implementation of schemes as may be entrusted to them including those in relation to the matter listed in the Twelfth Schedule.”

Art. 246 also suggests that the Legislature of a State may, by law, endow the Committees (the Wards Committees) with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to carry out the responsibilities conferred upon them including those in relation to the matters listed in the Twelfth Schedule.

But there are three issues of concern:

This article is not a statutory binding for the State Legislatures, it’s just indicative and the State has discretionary power ultimately.

The Twelfth Schedule is only illustrative; all matters listed therein neither need to be devolved, nor are they suggested to be exhaustive.

The schedule indicates only the subject-matters of functions, not the functions themselves that could be entrusted.

Urban local bodies are governments even if they are derivate of their respective State governments. Therefore, they will carry out some regulatory function.

3.2.1 Constitutional provisions regarding the financial duties of ULBs

While there is no reference to loans and user charges, there are laid down broad guidelines in other matters in the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act. The Art. 243X stipulates that, the Legislature of a State may, by law,

“(a) authorize a Municipality to levy, collect and appropriate such taxes, duties, tolls and fees in accordance with such procedures and subject to such limits;

(b) assign to a Municipality such taxes, duties, tolls and fees levied and collected by the State Government for such purposes and subject to such conditions and limits;

(c) provide for making such grants-in-aid to the Municipalities from the Consolidate Fund of the State;

(d) provide for constitution of such Funds for crediting all moneys received, respectively, by or on behalf of the Municipalities and also for the withdrawal of such moneys therefrom, as may be specified in the law. “

But again, these directions are not mandated for the State Legislature, and are pure discretionary. So far the experience of the State implementing these through ULBs is not very encouraging.

Article 243-Y stipulates that the Finance Commission (constituted under Article 243-I) shall review the financial position of the Municipalities and make recommendations regarding distribution of resources between the States and the Municipalities, determination of taxes, duties etc.; and grants-in-aid to the municipalities, among other matters.

The financial powers and functions of ULBs have been dealt with in-depth at a later part in this policy paper.

As part of the Reform Agenda, the Government of India (GoI) has developed a Model Municipal Law (MML) in 2003, National Municipal Accounting Manual (NMAM) in 2004, Solid Waste Management Rules (SWMR) in 2016 etc. to guide the states to enact municipal legislations, maintenance of accounts and delivery of services. The basic objective of the MML was to implement the provisions of the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA) in totality for empowerment of the Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and provide the legislative framework for implementation of the Ministry’s Urban Sector Reform Agenda. This initiative was expected not only to enhance the capacities of the ULBs to leverage public funds for development of urban sector but also in creating an environment in which ULBs can play their role more effectively and ensure better service delivery.

3.2.3 Effect of this connection on the working of Policies and Decisions taken

In many States, the functions are delegated to the ULBs through executive orders rather than transferred through a piece of legislation. Hence, they can be withdrawn easily. Even if they are not formally withdrawn, they can be effectively withdrawn or not delegated at all by instituting boards and authorities for municipal functions.

The ULBs cannot be formally superseded/ suspended. If the State Government dissolves a Local Body, then election to the same must be held within a period of six months. Moreover, the conduct of elections is entrusted to the statutory State Election Commission, rather than being left to executive authorities. It brought continuity to the elected body and development of bottom-up leadership.

3.3 The need for a ‘Bottom-up approach’ in Environmental Jurisprudence

The ‘problem of fit’ refers to the failure of social institutions to adequately match or align with the spatial, functional, temporal features or dynamics of the ecosystems. (Galaz, Victor & Olsson, Per & Hahn, Thomas & Folke, Carl & Svedin, Uno. (2008). The Problem of Fit among Biophysical Systems, Environmental and Resource Regimes, and Broader Governance Systems: Insights and Emerging Challenges. This is a common phenomenon especially in the cases of environmental jurisprudence. This is due to the characteristic of Environmental impacts and vulnerabilities of being extremely specific to a particular region and/or community. India has seen a localized climate disaster nearly every day in the first nine months of 2022, according to the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE).[1]

The relevancy of Environmental laws and the efficiency in implementation is dependent on the localized geographical parameters, market systems, and the vulnerability of those communities. Hence, to make the Environmental policies more effective, the ‘Bottom-up’ approach must be employed, instead of the ‘Top-down’ one. Policies that encourage bottom-up initiatives can allow the stakeholders to dictate their own priorities, enhancing their fit with social needs and improving the impact of these efforts (Brown 2003; Guerrero et al. 2015). In a recent study done in Bengaluru, a decentralized but interconnected system for lake governance was strategized and implemented, which proved to decrease the socio-ecological misfit to a large extent. This is a classic example of a ‘Bottom-up’ approach, and how effective it can be. [2]

Hence in order to study and comment on the efficiency and impact of environmental laws in the country and the effect they have on people and ecosystems, it becomes all the more relevant to study the powers dissipated to the local governing bodies of regions, the autonomy they have to legislate/amend the laws to suit the region, and the machinery they possess to implement the laws formulated by the State/Center.

India’s economic development propelled by rapid industrial growth and urbanization is the main cause of severe environmental problems that have local, regional and global significance. This economic development owing to industrialization has been concentrated in the Urban areas. [3]

The environmental laws are required to be highly efficient in especially the urban areas due to high density of industries, and the growing rate of transportation as well as industries/industrialization. Urban areas have a conducive environment for the Bottom-up approach, due to the high connectivity and accessibility of regions. To keep the economic transformation in line with the region-specific impacts of the pollution, it’s necessary to involve the local representatives in the policy making process and its implementation. Hence the role of the Urban local bodies becomes even more relevant.

3.4 Constitutional provisions for the bottom-up approach

The process of bottom-up planning was restored by constitution of the Ward Committees. Provisions for constitution and composition of Ward Committees were ensured vide Article 243S, as per the following:

“a) There shall be constituted Wards Committees, consisting of one or more Wards, within the territorial area of a Municipality having a population of three lakhs or more.

b) The Legislature of a State may, by law, make provision with respect to – – the composition and the territorial area of a Wards Committee; – the manner in which the seats in a Wards Committee shall be filled.

c) A member of a Municipality representing a ward within the territorial area of the Wards Committee shall be a member of that Committee.

d) Where a Wards Committee consists of – – one ward, the member representing that ward in the Municipality; or – two or more wards, one of the members representing such wards in the Municipality elected by the members of the Wards Committee, shall be the Chairperson of that Committee.

e) Nothing in this article shall be deemed to prevent the Legislature of a State from making any provision for the Constitution of Committees in addition to the Wards Committees.”

The Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) is formed at the municipal level to oversee project implementation. However, the SPV should have due control of implementing schemes in the environment of complex relationships.

Case studies for Bottom-up approach in India for implementing environmental laws:

India has implemented several environmental policies that encourage and provide for a bottom-up approach, like the National Biodiversity Act (2002) (available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/2046/1/200318.pdf ) National River Conservation Plan (NRCP), National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM), Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), to name a few.

Overall, these policies prioritize community participation and encourage the involvement of local bodies and stakeholders in decision-making processes.

Case Studies of ULBs in India implementing Environmental laws:

There have already been several localized efforts by Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in India for the implementation of environmental laws. Here are some examples:

Solid Waste Management in Surat: The Surat Municipal Corporation (SMC) implemented a solid waste management system that included waste segregation at source, door-to-door collection, transportation, and processing. The waste was processed at the Solid Waste Treatment and Disposal Facility (SWTDF), where the organic waste was turned into compost and the inorganic waste was recycled or sent to a landfill. As a result, Surat became a model city for solid waste management in India, with a 92% waste collection efficiency and no open dumping.

Rainwater Harvesting in Chennai: The Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CMWSSB) made rainwater harvesting mandatory for all buildings in the city in 2003. They also provided financial incentives for residents who implemented rainwater harvesting systems. As a result, the city’s groundwater levels have improved, and water scarcity during the summer months has reduced.

Greening of Bangalore: The Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) implemented a project to increase green cover in the city. The project included planting trees along roadsides and in parks, and encouraging citizens to plant trees in their homes and neighborhoods. As a result, Bangalore’s green cover increased from 17% in 2001 to 34% in 2014.

Plastic Ban in Maharashtra: The Maharashtra government implemented a ban on single-use plastic in the state in 2018. The ban included plastic bags, disposable plastic cups and plates, and plastic cutlery. The state also imposed fines and penalties for violations. As a result, there has been a significant reduction in plastic waste in the state.

Clean Energy in Delhi: The Delhi government implemented a program to promote the use of clean energy in the city. The program included providing financial incentives for rooftop solar installations and promoting the use of electric vehicles. As a result, the city’s air quality has improved, and there has been a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

3.5 Analysis of Current Environmental Legislation with respect to ULBs

The Environment (Protection) Act 1956 gives Central Government the power to constitute authorities if it considers necessary but doesn’t mention any role of the existing structures of local governments already which have already established [Sec 3(3)]

The entire Environment (Protection) Act 1956 has been drafted to give maximum authority and control to the Central Government. The underlying hierarchical tone of Act is quite evident. The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1974 stipulates the constitution of a State board, which, in turn, can constitute committees. Under Section-21(1) A of the Act, the State Government has the power to take samples of water from any stream or well or any effluent being discharged into such a stream or well, for analysis. Under Section-22(4) of the Act, the State Board further has the power to obtain a report of the result of the analysis by a recognised laboratory. But there is no mention of the role of Local Governing Bodies/Gram Panchayats/Municipal Corporation The Hazardous Waste Management (HWM) Act, 2016, defines the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders involved in the management of hazardous waste. Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) have a crucial role to play in the effective implementation of this act.

ULBs are responsible for implementing the HWM rules at the local level. They are responsible for identifying the sources of hazardous waste within their jurisdiction and ensuring that such waste is collected, transported, treated, and disposed of in an environmentally sound manner.

The specific roles and responsibilities of ULBs in hazardous waste management under the HWM Act include:

- Identification and notification of hazardous waste generating units within their jurisdiction.

- Issuing authorizations and permits to industries and establishments for the collection, transport, treatment, and disposal of hazardous waste.

- Ensuring that the hazardous waste generated within their jurisdiction is collected, transported, and treated in accordance with the HWM rules.

- Establishing and maintaining hazardous waste collection centers and storage facilities within their jurisdiction.

- Conducting periodic inspections of hazardous waste generating units to ensure compliance with the HWM rules.

- Ensuring proper disposal of hazardous waste within their jurisdiction and monitoring the functioning of common hazardous waste treatment, storage, and disposal facilities.

- Raising awareness among the public and industries about the importance of hazardous waste management and the need to comply with the HWM rules.

In summary, ULBs play a critical role in the implementation of the HWM Act in India. They are responsible for ensuring that hazardous waste is managed effectively at the local level and that the environment and public health are protected from the adverse impacts of hazardous waste.

3.6 Citizens’ Role in Environmental Jurisprudence

Under the ‘public interest litigation’ process, the Supreme Court of India and the High Courts have relaxed standing and other procedural requirements so that citizens may file suits even through a simple letter, without the use of a lawyer, and appear before the National green Tribunals.

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) can be filed against Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in India if their actions or inactions violate the rights of citizens or harm public interest. Some examples of issues against which PILs can be filed against ULBs are:

- Failure to provide basic services: PILs can be filed against ULBs for failure to provide basic services such as water supply, sanitation, garbage disposal, and street lighting.

- Illegal construction: PILs can be filed against ULBs for illegal construction of buildings, which may cause harm to public health, safety, and environment.

- Environmental degradation: PILs can be filed against ULBs for actions that lead to environmental degradation such as indiscriminate dumping of waste, pollution of water bodies, and destruction of green cover.

- Traffic congestion: PILs can be filed against ULBs for failure to address traffic congestion in urban areas, which affects the mobility and safety of citizens.

- Corruption: PILs can be filed against ULBs for corruption and misuse of public funds, which harms public interest and undermines the rule of law.

The process of filing a PIL against ULBs in India is similar to that of filing a PIL against any other public authority. The petitioner can approach the High Court or the Supreme Court with a written petition highlighting the issue and seeking appropriate relief. The court may issue notices to the ULB and other concerned parties, hear their arguments, and pass appropriate orders to ensure compliance with the law and protection of public interest.

3.7 Landmark Judgments related to the role of ULBs in Environmental Jurisprudence

No precise test has been formulated by the courts to define what constitutes a local matter. The general approach has been to evaluate the contested regulations on a case-by-case basis. But there have been several landmark judgments in India that have established the role and responsibilities of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in the country.

B.L. Wadehra v. Union of India (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/124028/ ) A petition was filed for directions to Municipal Corporation, Delhi and the New Delhi Municipal Corporation to perform their duties, in particular the collection, removal and disposal of garbage and other waste. The court issued directions to Municipal Corporation, Delhi and New Delhi Municipal Corporation regarding collection and disposal of garbage to keep the city clean.

Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985) (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/709776/ ) This case dealt with the issue of eviction of pavement dwellers in Mumbai. The Supreme Court held that the right to livelihood was a fundamental right under the Indian Constitution and that ULBs had a duty to provide basic amenities and shelter to the poor and homeless.

Municipal Council, Ratlam vs. Shri Vardhichand and others (1980) (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/440471/) In this case, the Supreme Court held that the ULBs had the responsibility to maintain cleanliness and hygiene in the city and to ensure the safe disposal of waste.

M.C. Mehta vs. Union of India (1987) (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1486949/ )This case dealt with the issue of pollution in the river Ganga. The Supreme Court held that the ULBs had a duty to ensure the prevention and control of pollution in their respective jurisdictions.

Delhi Development Authority vs. Delhi Bachao Andolan (2018) : In this case, the Supreme Court held that the ULBs had a duty to ensure that public land was not encroached upon and that the Master Plan of the city was implemented in a time-bound manner.

Kalyan Singh vs. State of Uttar Pradesh (2012) (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1869694/ )This case dealt with the issue of unauthorized construction in the city of Ghaziabad. The Supreme Court held that the ULBs had a duty to prevent unauthorized construction and to take appropriate action against violators.

These judgments have helped to establish the role and responsibilities of ULBs in India and have emphasized the need for them to work towards the development and welfare of citizens.

International Case study:

The Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy is a European initiative launched in 2008 by the European Commission with the aim of supporting and encouraging local governments to take concrete action to mitigate climate change and adapt to its impacts. The Covenant of Mayors is a voluntary commitment by cities and towns to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030 and to develop resilience to the impacts of climate change. Signatories to the Covenant pledge to develop and implement a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) that outlines their strategies and actions to achieve these goals. By signing the Covenant of Mayors, local governments commit to sharing their experiences and knowledge with each other and to work towards the creation of a low-carbon, climate-resilient society. The initiative also provides support and guidance to signatories through training, technical assistance, and access to funding. As of 2021, over 10,000 cities and towns across Europe have signed the Covenant of Mayors, representing a combined population of over 300 million people. The Covenant has also expanded beyond Europe and has been adopted by cities in other regions, including Africa and Latin America.

The Covenant of Mayors is a key initiative in the European Union’s efforts to involve local government bodies in addressing climate change and meeting its commitments under the Paris Agreement.

3.8 Analysis of the Maharashtra State Action Plan on Climate Change (MSAPCC) with respect to ULBs

The MSAPCC implemented by the State of Maharashtra is the pioneering example of how Climate Change can be prioritized in the State Agenda and implemented at the local government level.

The key recommendations have been categorized as follows, according to the domains relevant for Urban Communties and Management.

Water Conservation and Management: There are several existing policies and programs which are being implemented at the local level by our State Government, such as the Jal Jeevan Mission, National Water Mission, PMKSY, Atal Bhujal Yojana and Amrut Sarovar, and state water schemes like Jal Yukt Shivar 2.0. The enforcement of these programs is where the executive body falls short. Along with the quality, the coverage area of schemes like Amrut Sarovar (for restoration of water bodies and wetlands) should be increased and periodically monitored using software like GIS mapping system, etc. This can be facilitated through an inter-sectoral coordination and dialogue between Water Supply and Sanitation, Rural Development Department, Urban Development Department, Department of Water Resources, Agriculture and Soil Conservation while the Department of Environment and Climate Change extends necessary technical and knowledge management support towards water efficient models.

Waste Management: The Hazardous Waste management Rules, Swachh Sarvekshan, and Swachh Bharat Mission and Act stipulate for empowering the Local Government bodies with investigative and enforcement functions. But the Urban Local Bodies should strengthen efforts to reduce waste generation, especially single-use plastic, and stop the leakage of waste into ecosystems and improve the mechanisms for extended producer responsibility.

Biodiversity: There should be special fund allocation to strengthen the activities that protect critical ecosystems such as rivers, wetlands, mangroves, and coral reefs on priority.

Disaster management: Efforts should be made to mandate the representation, inclusion, and protection of the rights of the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. In the contect of Urban Metropolitan communities, this refers to the Slum areas and settlements which are categorised as ‘Vastis’. The ULBs need to strengthen the availability of training for disaster risk reduction and emergency response for youth volunteers. After the 2019 Flash floods in Pune, we now know how imperative it is to upgrade our Disaster Alert systems and mandate periodical drills.

Public health infrastructure: We need to reinforce the early warning systems/ health alerts to strengthen the health infrastructure and make it the first point of contact. Collaboration should be prioritised with Civil society to develop communication materials that could be disseminated widely through modern means that would be available for voluntary assistance and entrepreneurships in health-climate change-disaster.

Governance and Planning: The proposed ‘State-level Climate Change Cell’ comprises young people, multi-disciplinary experts including climate scientists, social workers, urban planners, engineers etc. and have representation of various regions of the state, with a decentralized model upto the district/ block levels. We also recommend appointing “Climate Resilience Fellows” and “paryavaran rakshaks” in every district and block along the lines of CM Fellows, and ASHA workers, to ensure last mile reach in the area of climate change and as a mechanism to engage with and promote climate focused programs. Provisions for financing the public participation process also needs to be considered. Climate Fellows at the District level can support in the implementation of SAPCC, and provide participatory training for community-based Climate Resilience planning, starting at school level including school safety planning and as special courses as well as youth skill development programs.

Along with this, the Government should incentivize household-level lifestyle changes, learning from the existing Government of Delhi model and with a view to promote responsible consumption, that feeds into the Mission LiFE targets.

Recently, the government of Kerala has also announced its plan to ensure that the state reaches its goal of using 100% renewable energy by 2040 and becoming net carbon neutral state by 2050, under its ‘Kerala State Action Plan on Climate Change’. This is a positive trend that is being seen, and the other states should take cognizance of it.

Chapter 4: An Overview of the Finances of ULBs

4.1 The State of Municipal Finances

Revenues of municipalities come from different sources but are limited in amount. Today, the total revenue of ULBs in India account for a meagre 0.75% of the country’s GDP, against cities of BRICS countries such as Brazil (8%) and South Africa (6.9%). This has led to a mismatch between authority and accountability in India.

Rao (1986) classified municipal revenue sources as follows:

a) municipal own revenue comprising tax and non-tax revenue.

(b) shared taxes with the state government.

(c) grants-in-aid from the state and central government; and

(d) borrowings from financial institutions

Funding from Union and State governments:

- Mandatory shared resourceswhich are based on the recommendations from the State Finance Commissions; The Government of India as per the Constitution has been making allocations to local bodies through the finance commissions. The tenth finance commission was the first to recommend grants for rural and urban local bodies.