Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink, by Arati Kumar-Rao, is a passionate environmentalist’s account of her journeys across India’s diverse landscapes for over a decade, and of the “slow violence” inflicted on the fragile environment and its impact on livelihoods.

Combining journalistic reporting and storytelling, the five-part book narrates stories from Rajasthan’s Thar desert, to the Gangetic plains and the Sunderbans, India’s western coastline, and Ladakh in the Himalayas.

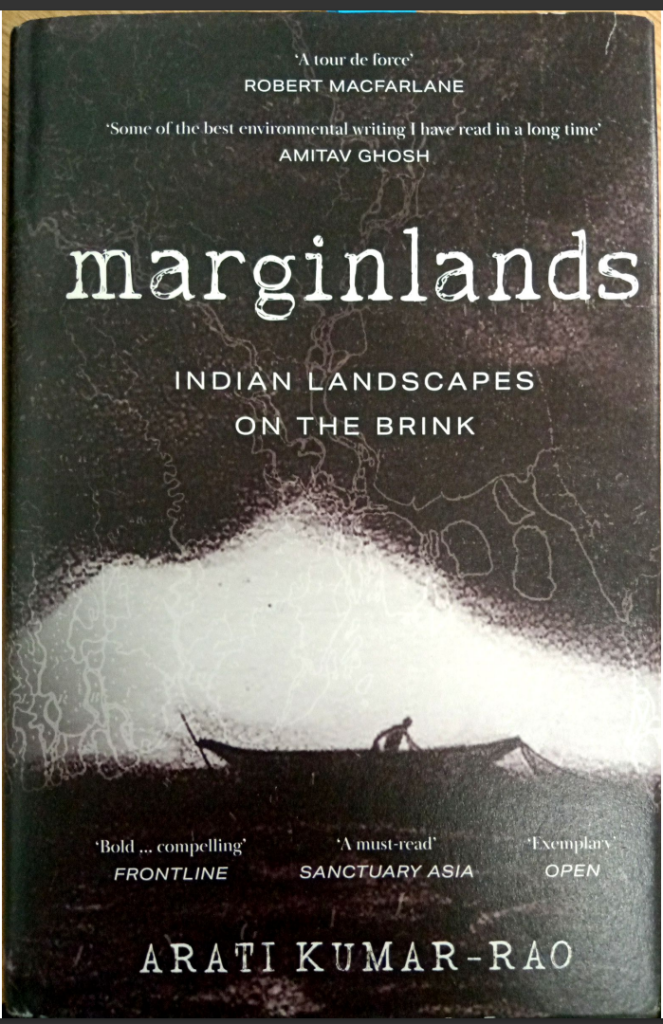

The book opens with black-and-white sketches of a river system and a shoreline at early dawn with beached catamarans and fisher folk solemnly walking home with their catch. Arati uses many such sketches, along with photographs, to bring alive her book’s subjects – the environment and its inhabitants.

The Prologue gives a peek into the author’s life in Bangalore, where she worked for a multinational firm, before quitting and venturing “into the uncertain world of environmental storytelling.” A photographer, author and National Geographic Explorer who is on BBC’s 2023 list of 100 inspiring and influential women from around the world, Arati then goes on to recount her early years with her parents in the eighties’ Mumbai; reading Salim Ali’s Book of Indian Birds; and going on bird-watching trips to the Sanjay Gandhi National Park with her father, who was an engineer by profession but was convinced about the efficacy of renewable energy “long before climate change and clean, green energy became catchphrases”.

The account she gives of her father – who was “dead set against large dams” and had “marched with protesters” against their construction – also reveals the source of her inspiration to give up her “safety net” and fully commit to environmental storytelling. She explains how after deciding to become a storyteller and “with no idea how to go about it”, she “logged on to Facebook and Twitter to connect with journalists, editors, wildlife biologists, hydrologists and environmental activists” before finally dipping into her savings and flying out to Rajasthan’s Thar desert to pursue her story. With stories and anecdotes, she narrates how one thing led to the other and culminated in this book.

In Part 1, Arati explores the Thar desert, its dunes, and presents the daily lives, wisdom and histories of the desert people as seen through the eyes of a local shepherd farmer, Chhattar Singh, who tells her that she can’t tell her story “if you don’t see for yourself how the desert changes with the seasons and how my people adapt to it.” So, after “observing the desert, living amidst its people” and “walking with the shepherds”, she writes about the secrets and “magic” of survival in a place with no “water in sight” but where locals know when they see the hint of water under the dunes, and how mining is turning the rich desert ecosystem into a “wasteland”.

Part 2, ‘Veins of our Land’, takes the reader to eastern India. Here, the author traces the course of the river Ganga from the Himalayas to the plains it fertilises downstream and the ecosystems it supports. The chapter, titled ‘The Farakka Folly’, explains how the river is “baulked of its natural course by the Farakka Barrage”, which was built to save the Calcutta port but instead, in the words of a local, Tarikul-bhai, “wreaked havoc across northern Bengal” with recurrent floods forcing some people to move homes “seventeen times in the last two decades.”

Arati narrates how as the “newly independent nation pushed forth its development mission”, damming and other human activities on the rivers slashed the endangered Gangetic dolphin’s habitat by “80 per cent” and even depleted the famed hilsa fish of Bengal to the point where locals speak of it “with a forlorn nostalgia as this king among fish disappears from its habitat.” The book takes you deep inside the Sundarban mangrove forests and the precarious lives of people living in the mudflats that have for centuries provided “fertile waters for fishing, forests of timber, and flowers for wild honey.”

In Part 3, ‘An Eroding Margin’, the writer traverses India’s western coast between Thiruvananthapuram and Mumbai and wonders “what we are doing unto the wild coastline of India.” She attributes Mumbai’s flood woes to both natural and human induced reasons and the damage caused to the coastline by land reclamation from the Arabian Sea and the destruction of mangroves. She reasons that Mumbai stands to lose not only its rich marine biodiversity but also puts at risk its first human occupants – the traditional fishermen.

Going south, Arati explains how human activities such as constructing seawalls and mining of sand along Kerala’s coast have led to entire fishing communities living in fear of their homes being swallowed by the sea due to coastal erosion. Here again, she points to the “consequences of blocking rivers”, with forty-one of those originating in the Western Ghats witnessing diminishing water and sediment flows, thus impacting coastal health; another consequence she points to is flooding, such as the one Kerala saw in 2018.

Part 4, ‘The Third Pole’, takes you to the Himalayan ecosystem in Ladakh, a place with “negligible” carbon footprint but bearing the brunt of climate change. Arati gives first-hand accounts of the floods that have hit the region and claimed many lives in recent times. As the Magsasay Award-winning engineer and educator Sonam Wangchuk tells her: “Ladakhis had no living memories of floods.”

In the Epilogue, the author narrates how experiencing the fragile landscapes first-hand revealed to her their real state and that of its inhabitants. The book ends with the quote: “The hardest thing of all to see is what is really there.”

Book summary by Pradeep Nair, Sr Editor, PIC